My Framework for Thinking About Bitcoin (and Gold)

It's not about ideology, it's about understanding the financial system.

Since launching this Substack, I've mentioned Bitcoin a few times, but I haven't really gotten into why I think it warrants serious consideration as part of a modern investment portfolio. Plenty of pundits have written books on Bitcoin's technology, game theory, and any other aspects you can think of. I'm not going to replicate that or attempt a bulletproof technical argument here. Instead, I want to provide the framework – the macroeconomic backdrop – for why holding Bitcoin makes logical sense to me.

Setting the Scene: Why Hard Assets Matter

In a previous post, I might have ruffled a few feathers amongst our Austrian Economics friends by questioning the practicality of a full-blown hard money system. But where I can definitively agree is on the enduring value of hard assets. A hard asset is simply something that is difficult, costly, or impossible to create more of.

Traditionally, this meant physical things like gold – with its supply limited by geology and the effort of mining. Today, Bitcoin has forcefully entered the conversation, often dubbed "digital gold" due to its mathematically enforced, programmed scarcity. Other examples could include things like truly rare art, certain gemstones, or even prime real estate in desirable locations. The core idea is scarcity that exists outside the whims of political or monetary policy. This scarcity helps these assets potentially hold value over long periods, acting as a store of wealth when easily-printed currencies lose their purchasing power.

The Unavoidable Truth: Currency Debasement

Why is holding scarce assets useful? Because we live in a thoroughly financialized world dominated by "fiat" currencies – money created by government decree and managed by central banks. The US dollar sits at the top as the global reserve currency, meaning it underpins much of international trade and serves as the primary asset held in reserve by most other countries (often in the form of US government debt, or Treasuries).

Now, here's the fundamental concept, the one thing you must understand about this system: over time, the value – the purchasing power – of these fiat currencies consistently decreases. Think about it: the dollar, the Euro, the Pound, the Kiwi dollar... they all buy less today than they did 10, 20, 50 years ago. This isn't a conspiracy theory; it's largely by design, driven by inflation targets and monetary policy aimed at encouraging spending and managing debt. This gradual erosion of value is currency debasement. I’m not here to argue for or against this concept - it is simply a fact investors must understand.

Historically, the US dollar had ties to gold, but these were progressively weakened. Key moments include the Gold Reserve Act of 1934 (revaluing gold significantly higher against the dollar), the Bretton Woods agreement in 1944 (pegging other currencies to the USD, which was pegged to gold), and crucially, the "Nixon Shock" of 1971, when the US unilaterally ended the direct convertibility of dollars to gold for foreign nations. This ushered in the pure fiat standard we've known ever since, where currency value rests solely on government promises and market confidence.

The Game Changer: 2008 and the QE Era

Then came the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008. When complex debt products tied to US mortgages (Mortgage-Backed Securities, or MBS) imploded, they threatened to take the entire interconnected, and frankly poorly risk-managed, global financial system down with them. In response, the US Federal Reserve (and other central banks) stepped in not just as a lender, but as a buyer of last resort. They started purchasing massive amounts of toxic MBS and government bonds directly from banks, injecting newly created electronic money into the system to prevent a complete meltdown.

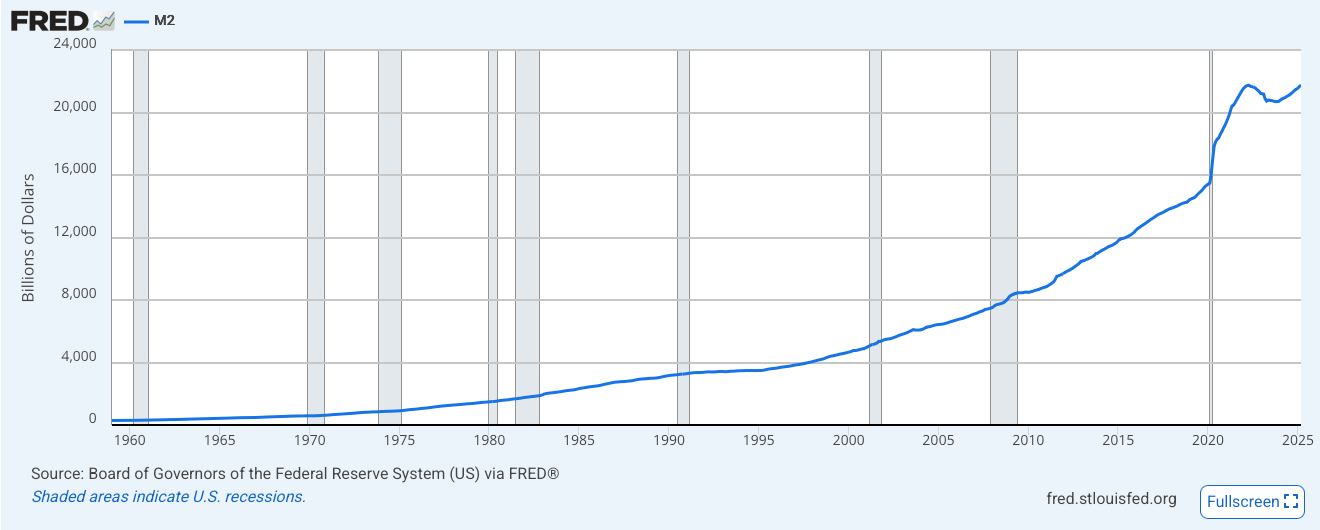

This had a fancy name – Quantitative Easing (QE) – but boiled down to creating money out of thin air to buy financial assets and prop up the system. While initially framed as a temporary emergency measure, here we are, well over 15 years later, having seen QE deployed again during COVID and other stresses, meanwhile being unable to unwind the previous dose in-between. It's clear they crossed the Rubicon in 2008. There's no going back to a pre-interventionist world. Just look at a long-term chart of the US M2 money supply below – that steepening curve isn't reversing. The trend is similar globally.

Now here is the same chart with two trend lines added. As you can see from the R value both are a good fit, but the exponential one (the upper) is the better fit. It projects that in ten years the US M2 money supply will double again.

As a point of reference, between March 2020 and the end of 2021 (when M2 exploded) the S&P 500 doubled (bitcoin was up more than 1000%).

Why There's No Turning Back

Why are QE and an expanding money supply now seemingly permanent features? Because the modern financial system, heavily reliant on credit cycles and debt, runs on rate-of-change and expectations. Suddenly stopping or, heaven forbid, reversing the long-term growth trend of the money supply wouldn't just feel like gentle braking; it would feel like slamming into a brick wall. Refer to the above chart again and notice when the money supply reduced in 2022 to mid 2023. The S&P 500 dropped about 25% during that time and the needle barely moved on total M2 (bitcoin was down 75% around that time).

It would trigger a brutal credit contraction, likely causing a severe recession or depression. Financial markets, addicted to liquidity, would almost certainly crash. The political instability would be immense. I simply do not believe any politician or central banker in today's world has the political resolve – or mandate – to willingly inflict that kind of short-term pain for long-term theoretical 'soundness'. Any leader overseeing such a contraction would face immediate public backlash and electoral oblivion. The political incentive structure overwhelmingly favours intervention and continued monetary expansion when faced with crisis.

What This Means for Investors

So, if you accept the premise that currency debasement is an inherent feature, likely accelerated post-2008, what does that mean for how you store your wealth long-term?

First and foremost, it strongly suggests you don't want to hold large amounts of your savings in cash or government bonds yielding less than the true rate of purchasing power loss over long horizons.

In my opinion, the purest way to protect against (and potentially benefit from) this relentless currency debasement theme is through owning scarce, non-sovereign assets whose supply cannot be easily inflated by political decisions. Historically, that's been gold. It has millennia of history as a store of value and monetary medium, and it will likely continue to play that role.

But Bitcoin is the disruptive new kid on the block. It's designed from the ground up as the world's first truly scarce digital asset, with its 21 million coin limit permanently fixed in code and enforced by a globally distributed, decentralized network. This makes it incredibly resistant to censorship or changes in its supply schedule – arguably making it the 'hardest' asset ever known in terms of verifiable supply limitation. (You'll have to take my word on some of the deeper technical properties here or do your own research). While other cryptocurrencies exist, Bitcoin's first-mover advantage, decentralisation, and powerful network effect (where value increases as more people use and trust it) make it unlikely it will ever be usurped as the dominant, credibly scarce digital store of value.

So, if you compare an asset whose supply is designed to inflate indefinitely (like the USD) to one whose supply is mathematically fixed (like Bitcoin), the long-term outcome seems almost inevitable: the dollar-price of the fixed-supply asset must go up over time (though you should correctly argue it's the dollar going down relative to Bitcoin).

There's even a credible case to be made that as Bitcoin gains adoption and recognition, it may start to demonetize gold – not replace it entirely, but capture some of gold's massive monetary premium because Bitcoin offers potential advantages in portability, divisibility, verifiability, and ultimate scarcity assurance. This potential is why, regardless of your preference, holding both might make sense, though I personally lean more heavily towards Bitcoin given its digital nature and asymmetric upside potential. Bitcoin also often exhibits a "risk-on" characteristic, experiencing strong gains during periods of high liquidity and market booms, adding another dimension to its behaviour compared to gold.

Of course, there are other (more productive) ways to hedge debasement. Owning shares in high-quality, dominant businesses (think Nvidia, Meta, Google, etc. – companies with unique products/networks) is another effective strategy, as you own a piece of real productive capacity whose nominal earnings tend to rise with inflation over time. But stocks carry specific business risks (competition, management errors, disruption) and valuation risks (paying too high a price) that are different from owning a pure bearer asset like Gold or Bitcoin.

In Conclusion

Financial markets are noisy. Economic cycles come and go. Specific stocks, even great ones, face individual risks. But underneath all that noise is, in my view, a fundamental, multi-decade trend: the ongoing debasement of fiat currencies driven by political necessity and post-GFC policy shifts.

While owning productive assets like stocks is absolutely crucial for wealth building and portfolio balance, the purest investment plays specifically targeting this long-term debasement theme are gold and, in my opinion even more compellingly for the digital age, Bitcoin. Understanding this framework is key to how I think about navigating the financial world we live in.

Nice article

I presume you advocate BTC as a store of value rather than a currency to transact? The fees associated with moving BTC around are perilously high.

I know that each coin is divisible (sats), but with the limited supply and that there a large number of bitcoins that have been lost forever - is this lack of ‘liquidity’ going to be a drawback?